Quick Link 2

Jeff Probst to DA Adam Schiff, by way of Mission: Impossible, the Star Trek minyan, Golden Eyeball Awards, Sam Elliott's mustache, the history of the term "self-destruct," and the lost joys of the fax

In the early 1990s I fell into a sordid little obsession with the ridiculous, glorious TV series Mission: Impossible (1966-1973)--or, as my partner called it, at first sarcastically but then she got sucked in too, “Mish-UN! Co-LON! . . . Impossible.” The show, in syndication on the brand-new cable outlet FX, was “hosted” by Jeff Probst, later of Survivor, who would briefly introduce each episode from what appeared to be not a TV studio but someone’s hip (or anyway far-hipper-than-mine) apartment.

In 1960s TV, shot hurriedly from scripts constantly under construction, with the expectation of 25 or more episodes per season, flubs—continuity errors, plot holes, inconsistencies—occurred often. In M: I the tendency was exacerbated by the difficulty of shoehorning byzantine plots into fifty minutes. And by an additional peril: many episodes took place in imaginary countries, often Eastern European or Latin American, in which half-familiar invented languages (nicknamed Gellerese after series creator Bruce) were spoken. As a result, IM Force operatives often encountered metal canisters labeled “Gäz” or the like—a word that read as foreign without straining viewers’ ability to understand whether the tank’s contents could, you know, blöew uup Willy and Barney. A car marked “Poliizia” might pursue IM Force personnel—occupying a panel van whose previous company affiliation was dimly legible beneath the spraypaint--past, say, a Rexall’s. Why are crypto-Soviets in an American patrol car, wearing Nazi-like uniforms, chasing a panel van formerly from “Busted Pipe Plumbing” past a chain drugstore in the nation of “Veyska”? Best not to question, viewer, given the complexities of geopolitics.1

Interaction with viewers was a big element of FX’s brand strategy, and Probst started asking viewers to note and send in the glitches they saw. For me, the turning point into obsession came when they invented something called the Golden Eyeball Award—and better yet, created a physical avatar for the coveted distinction. It looked like a three-dollar bowling-league-participation trophy with a papier-mâché eyeball either pressed over the figure of the bowler, so as to make him a kind of popsicle stick, or glued onto the base after someone broke off the gold-plastic Dick Weber. (My TV set was small and blurry, as is my memory, so take this description of the award with the appropriate grain of salt.) Viewers were invited to fax in the mistakes they spotted and—if chosen—to have their names announced as Golden Eyeball winners.2

I created a couple of personas, settling finally on “Wayne Barrow, Baton Rouge, Louisiana,” and began sending near-daily faxes. (Mea culpa: I may owe The Southern Review a few dollars—and the ghosts of Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks a few abject apologies—for all this.) Reader, it is not immodesty but the journalist’s responsibility to give credit where it’s due that makes me note: The keen-eyed Mr. Barrow earned more than one ophthalmic bowling dude.

One of the pleasures of the Golden Eyeball Award was that submitting the fax had to be its own reward; it was hit-or-miss whether you—or rather Mr. Barrow—would win, and even if he did, it wasn’t a sure thing that he would hear the news. FX wasn’t going to mass-produce or ship around the country its homemade trophy, so you—he!—discovered the triumph only if he tuned in in time to hear his name called on air. (The FX of those days was remarkably like FM radio, only national rather than local.)

I had a vague recollection of M: I’s final season or two from childhood, and I remembered especially the ubiquitous, jaunty theme by Lalo Schifrin—in part because I, and virtually every kid I knew, would hum it while pretending to do all kinds of covert missions in and around the house, many of these involving forbidden snacks. (Schifrin said that the theme’s unusual 5/4 timing reflected his desire to write not for human beings, who were said to prefer 2/4 time for its danceability, but “for people from outer space who have five legs.”) When in early adolescence, in pursuit of spycraft skills, I decided to learn Morse code, one of my reasons for doing so was that I read that Schifrin had incorporated the Morse code for “MI,” two dashes followed by two dots, as the theme’s main beat, a covert op I found irresistibly cool. (Not so cool, apparently, that I didn’t flunk the mission. Of Morse code I retain exactly two letters: M and I.)

But what I remembered most of all, and what it turned out almost everyone remembered vividly from the show—whether they’d watched it or not—was the scene at the start of every episode that went, almost verbatim, “Good morning, Mr. Phelps. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is . . . Should you or any member of your IM Force be caught or killed, the Secretary will disavow all knowledge of your actions. Good luck, Jim. This tape will self-destruct in five seconds.”

A big part of Mission: Impossible’s allure from the start had to do with the way it married impossibly convoluted and variable plans with rigid formula. Every episode began with the so-called “tape scene,” which was followed for most of the first season and some of the second with what was called a “dossier scene,” in which the IMF leader would paw through a sort of Sears spy catalog to select the agents to deploy for this particular mission. (These included, in one memorable episode from season 2, a cat.) Before long, though, the scene lost its drama because a core cast emerged: Greg Morris as engineering and technical genius Barney Collier; Peter Lupus as weightlifting (and chin cleftiness) world champion Willy Armitage, who often served among other duties as the IMF’s grunt or roustabout; the glamorous spy Cinnamon Carter, in which role Barbara Bain would win three straight Emmys; and master of disguises Rollin Hand, played by Bain’s real-life husband Martin Landau. The third scene (second, once the dossier scene fell away) was always in an apartment where the group was working out the details of the plan and practicing any special skills required.3

The opening “tape scene” is so well-known, so oft imitated or quoted or parodied in pop culture, that many people believe the word “self-destruct” was coined for the show. (In fact, it dates back to 1958, so M: I merely popularized it.) It’s a trope so closely identified with the series, and with the silver-haired, blue-eyed Peter Graves, that it’s hard to remember that the scene was quite different at the outset. For one thing, the tape—especially in season one—didn’t usually self-destruct. Sometimes it “decomposed,” or “destroyed itself,” or some other term; often, the tape had to BE burned or doused with acid or otherwise annihilated. There was variation in how much time would elapse (five seconds, ten, three and a half eons); the time of day changed. Global apocalypses being what they are, pressure-wise, the IMF didn’t always get the choice to accept their mission or not; even the actor who provided the disembodied voice of the instruction-giver, Bob Johnson, didn’t bring quite the same timbre and gravitas in some early episodes that he achieved later.

One reason for the later near-standardization of the verbiage in these scenes was simple frugality. Tape scenes required an extra location; extra expenditure of imagination and script-writing time; even the simple destruction of the tape recorders was expensive. (Presumably those scenes might also tack on chemical costs, insurance, maybe even a fire marshal’s wage.) In season two they began filming all the “tape scenes” at once, at the season’s beginning, and then recycling them; one well-known scene in a photomat was used at least three times, scattered across seasons.

But the most shocking revelation, for me, was that the person being wished “Good afternoon” in that first season wasn’t Jim Phelps at all; it was Dan Briggs. Which was like discovering that someone had played Columbo before Peter Falk or Lucy before Lucille Ball.

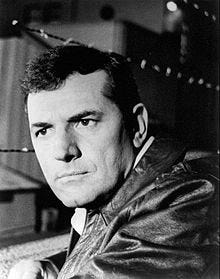

So who was the Wally Pipp to Graves’s Lou Gehrig? The actor who led the IMF that first season was Steven Hill. Born Sol Krakovsky in 1922, Hill had debuted alongside Marlon Brando in Ben Hecht’s 1946 play A Flag Is Born (which advocated for the birth of Israel), and he was considered by some as Brando’s great rival. Future co-star Martin Landau wrote that when he arrived in New York, “there were two young actors: Marlon Brando and Steven Hill. A lot of people said Steven would have been the one. He was legendary—nuts, volatile, mad—and his work was exciting.” Hill’s big break came on Broadway in Mister Roberts, in which his small role expanded when he improvised dialogue that was added to the show. Over the next fifteen years he would play, among many others, Sigmund Freud, Bartolomeo Vanzetti (of Sacco and), and the mobster Legs Diamond.

Hill was deadly serious about his Orthodox Jewish faith, and his M: I contract stipulated that the show would work around his religious observances. In practice, though, beleaguered directors were often either ignorant of what had been agreed to or knew the terms and tried to trample them anyway. This was flatly unacceptable to Hill, who observed all holidays and needed to leave the set by 4 pm on Fridays to be home by the beginning of the Sabbath. (An illustration of Hill’s seriousness around the subject: William Shatner, then shooting Star Trek on an adjacent lot, once burst into a producer’s office to press him into service; Hill, in search of a minyan, had invaded the USS Enterprise to ask “How many Jews do you have in Star Trek?” He’d recruited Shatner and Leonard Nimoy and sent them looking for others to round out the required ten.)

At first, it seems, the producers of Mission: Impossible did make some effort to work with and around Hill. When, given the tight schedule, filming encroached on the Sabbath, they improvised. After the tape and dossier scenes, Briggs might explain that he couldn’t go along on the mission because they were likely to encounter a villain who could recognize him . . . or because of the threat of exposure he would have to work in disguise—which allowed a guest actor to stand in for the bulk of the episode, with Briggs peeling off the latex face of the guest star at the episode’s end to become himself again. These adjustments were awkward—maybe even intentionally so, in order to give Hill encouragement to cave to producers’ demands in exchange for the more prominent role he’d signed up for. The temperament that Landau alluded to—“nuts, volatile, mad”—didn’t help; not for nothing was Hill described, in one article of the time, as “Hollywood’s Most Talented Curmudgeon.” The producers cajoled, pressed, threatened; Hill balked, in one case simply leaving the set mid-filming.

As one might expect, the combination of the producers flouting the contract (with the disdain for Hill’s faith that implied) and Hill’s angry inrtansigence soured relations fast. It came to a head during the filming of the season’s twenty-third episode, when Hill refused to climb what he considered to be a dangerous high staircase into some rafters. The producers wrote him out of the episode altogether, even re-filmed the tape scene so that Cinnamon received the mission instructions (the only time in the series run when the IMF would have a woman leader, I think) . . . and then radically curtailed Hill’s role in the season’s five remaining episodes. The rift was so deep and so bitter that, Hill said later, he only found out he was being replaced by Graves (whose brother, James Arness, was in the midst of his twenty-year run in one of the most popular roles on television, Marshall Matt Dillon on Gunsmoke) when he read it in Variety.

After his departure from M: I, Hill moved to an Orthodox community near New York City and withdrew from acting for a decade and a half. He wouldn’t return until the early 1980s, with roles in Barbra Streisand’s Yentl and Neil Simon’s Brighton Beach Memoirs. He wouldn’t resume work in series TV until 1990, when he began the role he is by far best known for, gruff and grumpy district attorney Adam Schiff on Law & Order, a character he would play for ten years before retiring in 2000. As Schiff, Hill was able to reverse the Wally Pipp curse; many people think that he was the original Law & Order DA, but in fact he replaced veteran actor Roy Thinnes, who’d played the DA in the pilot but was committed to a Dark Shadows reboot by the time Law & Order began filming its first season.

Hill died on August 23, 2016.

The member of the crew whose job it was to spray-paint stenciled block letters onto objects got a workout in the early seasons; I would guess that M:I is TV history’s untouchable record-holder for thing-labeling—possibly even if you count Wile E. Coyote v. Roadrunner cartoons.

About “faxed”: This now-dead technology has an M: I link. By the time the late-1980s reboot of the show (and then the movie franchise) came around, the clumsy, hissy audiotapes of the mid-1960s were no more, so the early-show warning to Mr. Phelps switched over from “This tape will self-destruct” to “This message will self-destruct.” Similarly, faxes pretty-much self-destructed over the ten years after my correspondence with Mr. Probst: a shame, in a way, because I loved their slowness and noise and the way the original came through the arduous transmission process changed—hot to the touch, in some way dubiously reconstituted, like something that had been through the Star Trek transporter twice and might not be quite the SAME anymore. And when you received one, it always came in the form of hot, light, ultra-smooth paper that curled (and often fell to the floor) in a scroll or diploma shape.

The cast was generally pretty stable. Morris and Lupus stayed throughout the show’s run, though the producers did TRY in season 5 to replace the lovably stiff Willy with, of all people, the pre-mustache beta version of the world’s handsomest man, Sam Elliott—only to be surprised by bitter complaints from viewers who loved having a grunt to identify with. Landau, who started season one as a guest-star and became part of the permanent cast the following year, was replaced in season four by Leonard Nimoy. Bain left at the same time, and no one seemed able to fill her shoes. Season four relied on a parade of guests, the only recurrent one being Lee Meriwether. Subsequent seasons featured Lesley Anne Warren, Lynda Day George, and others.